There has been a continuous debate about harmful effects of Electromagnetic Radiations ever since they came into existence. Most of the research results suggest that there are no harmful effects, if the rules and regulations are followed. But there is a small body of research that suggests that there might be some harmful effects and more research needs to be carried out. This is particularly important now as 5G Wireless Technology is being rolled out around the world and it uses millimeter waves for which we have limited data. Also, 5G would be using much smaller cells meaning that base stations would be closer to human beings.

Tag Archives: Antenna Array

Massive MIMO and Antenna Correlation

Some Background

In a previous post we calculated the Bit Error Rate (BER) of a Massive MIMO system using two different channel models namely deterministic and probabilistic. The deterministic channel model is derived from the geometry of the array (ULA in this case) and the distribution of users in the cell. Whereas probabilistic channel model assumes that the channel is flat fading and can be modeled, between each transmit receive pair, as a complex, circularly symmetric, Gaussian random variable with mean of zero and variance of 0.5 per dimension.

Continue reading Massive MIMO and Antenna CorrelationFundamentals of a Rectangular Array – Mathematical Model and Code

Background

In the previous few posts we discussed the fundamentals of Uniform Linear Arrays (ULAs), Beamforming, Multiuser Detection and Massive MIMO ([1], [2], [3], [4]). Now we turn our attention to more complicated array structures such as rectangular, triangular and circular. We still assume each element of the array to have an isotropic or omni-directional (in the plane of the array) radiation pattern. The mathematical models for more complicated radiation patterns are an extension of the what is developed here.

Square and Rectangular Arrays

In this post we consider a square array which is a special case of rectangular array. We build up from the most basic case of a 2 x 2 array and derive the equation of the resultant signal, which is simply the summation of the individual signals received at the four array elements. Later on we give the MATLAB code which can be used to plot the radiation pattern of any size rectangular array.

Derivation of the Array Pattern

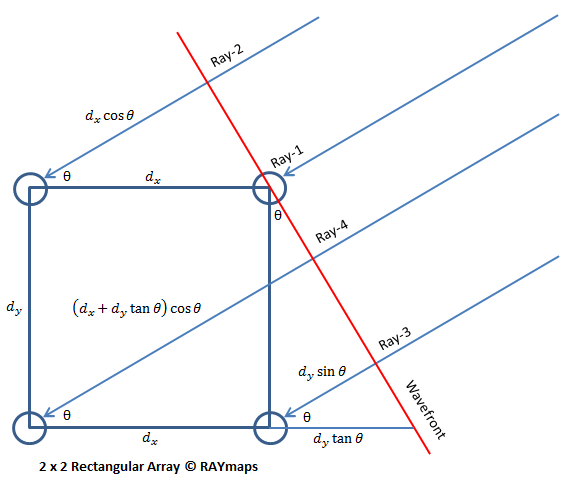

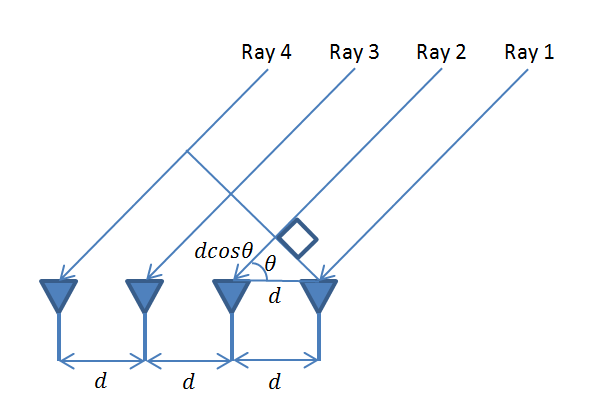

Lets consider a plane wave impinging upon a 2 x 2 receive array. The source is considered to be in the far field of the receive array making the plane wave assumption to be realistic. The equations for the received signal at the four array elements are given below. Please note that since the combined signal only depends upon the relative phase of the four components we assume the phase at the wavefront (red line in the figure below) to be zero. Also note that we have assumed that dx=dy=d.

r1=1

r2=e-j2πdcos(θ)/λ

r3=e-j2πdsin(θ)/λ

r4=e-j2πd(cos(θ)+sin(θ))/λ

The resultant signal can then be written as:

rt=r1+r2+r3+r4

In general for an N x M array the resultant signal can be written as:

rt=∑∑ e-j2πd(ncos(θ)+msin(θ))/λ

When the array is not square i.e. the separation along the x and y axes is not the same we have:

rt=∑∑ e-j2π(ndxcos(θ)+mdysin(θ))/λ

The range of n and m is 0 to N-1 and 0 to M-1 respectively.

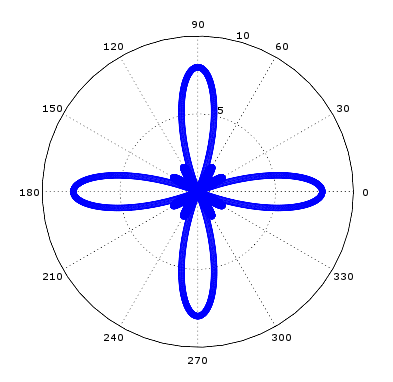

8 x 8 Square Array Radiation Pattern

MATLAB Code for a Rectangular Array

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

% SIMPLE RECTANGULAR ARRRAY

% WITH N x M ELEMENTS

% COPYRIGHT RAYMAPS (C) 2018

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

clear all

close all

f=1e9;

c=3e8;

l=c/f;

dx=l/3;

dy=l/3;

theta=0:pi/1800:2*pi;

N=8;

M=8;

r=0;

for n=1:N

for m=1:M

r=r+exp(-i*2*pi*(dx*(n-1)*cos(theta)+dy*(m-1)*sin(theta))/l);

end

end

polar(theta,abs(r),'bo-')

title ('Gain of a Uniform Linear Array')

Discussion of Simulation Results

In the above code we have assumed a carrier frequency of 1 GHz which gives us a wavelength of 0.3 meter. The element separation along the x and y axis is assumed to be 0.1 meter (lambda/3). The total number of elements is 8 x 8 = 64. The maximum gain obtained is equal to 8 on the linear scale or 9 dB on the logarithmic scale. The radiation pattern has four peaks which does not make this array structure to be of much practical use. More complex array structures resulting in more desirable radiation patterns will be discussed in future posts.

Note:

Please note that we have simplified the problem significantly by assuming an omnidirectional pattern of the array elements and plotting the composite radiation pattern only in the plane of the array. In reality the array elements do not always have an omnidirectional radiation pattern (one popular antenna that does have an omnidirectional pattern is a dipole) and we have to plot the 3D pattern of the array (or cuts along different planes) to get a better understanding of the characteristics such as Half Power Beamwidth, First Null Beamwidth and Side Lobe Level etc. More on this later.

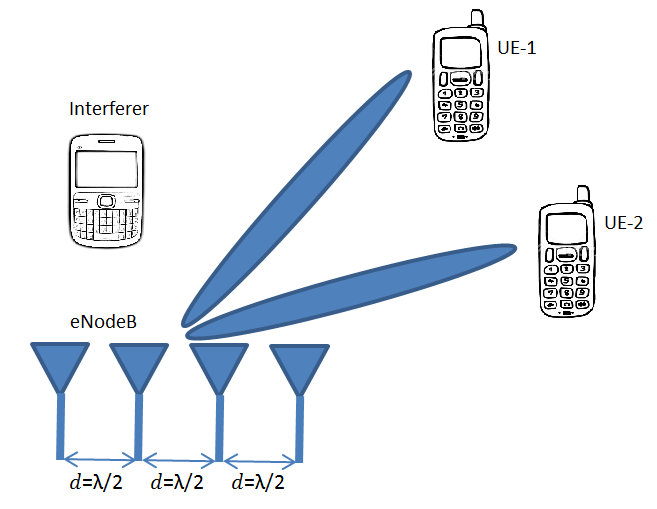

Fundamentals of Linear Array Processing – Receive Beamforming

In the previous two posts we discussed the fundamentals of array processing particularly the concept of beamforming (please check out array processing Part-1 and Part-2). Now we build upon these concepts to introduce some linear estimation techniques that are used in array processing. These are particularly suited to a situation where multiple users are spatially distributed in a cell and they need to be separated based upon their angles of arrival. But first let us introduce the linear model; I am sure you have seen this before.

x=Hs+w

Here, s is the vector of symbols transmitted by M users, H is the N x M channel matrix, w is the noise vector of length N and x is the observation vector of length N. The channel matrix formed by the channel coefficients is deterministic (as opposed to probabilistic) in nature as it is purely dependent upon the phase shifts that the channel introduces due to varying path lengths between the transmit and receive antennas. The impact of a channel coefficient can be thought of as a rotation of the complex signal without altering its amplitude.

This means that the channel acts like a single tap filter and the process of convolution is reduced to simple multiplication (a reasonable assumption if the symbol length is much larger than the channel delay spread). The channel model does not accommodate for path loss and fading that are also inherent characteristics of the channel. But the techniques are general enough for these effects to be factored in later. Furthermore, it is assumed that the channel H is known at the receiver. This is a realistic assumption if the channel is slowly varying and can be estimated by sending pilot signals.

So going back to the linear model we see that we know x and H while s and w are unknown. Here w cannot be estimated since it’s random in nature (remember what the term AWGN stands for?) and we ignore it for the moment. The structure of s is known. For example if we are using BPSK modulation then the m symbols of the signal vector s can either be +1 or -1. So we can start the process of symbol detection by substituting all possible combinations of s1, s2…sm and determine the combination that minimizes

||x-Hs||

This is called the Maximum Likelihood (ML) solution as it determines the combination that was most likely to have been transmitted based upon the observation.

Although ML is conceptually very appealing and yields good results it becomes prohibitively complex as the constellation size or number of transmit antennas increases. For example for 2-Transmit case and BPSK modulation there are 2^(1 bit x 2 antennas)=2^2=4 combinations, which seems quite simplistic. But if 16-QAM modulation is used and there are 4-Transmit antennas the number of combinations increases to 2^(4 bits x 4 antennas)=2^16=65536. So we conclude that ML is not the solution we are looking for if computational complexity is an issue (which might become less of an issue as the processing power of devices increases).

Next we turn our attention to a technique popularly known as Zero Forcing or ZF (the origins of the name I still do not know). According to this technique the channel has a multiplicative effect on the signal. So to remove this effect we simply divide the signal by the channel or in the language of matrices we perform matrix inversion. Mathematically we have:

x=Hs+w

H-1x=H-1Hs+H-1w

H-1x=s+H-1w=s̄

So we see that we get back the signal s but we also get a noise component enhanced by inverse of the channel matrix. This is the well-known problem of ZF called Noise Enhancement. Then there are other problems such as non-existence of the inverse when the channel H is not a square matrix (which only happens when the number of transmit and receive antennas is the same). The inverse of H also cannot be calculated if H is not full rank or determinant of H is zero. So we now introduce another technique called Least Squares (LS). According to this the signal vector can be estimated as

s̄=(HHH)-1HHx

This is also sometimes referred to as the Minimum Variance Unbiased Estimator, as described by Steven M. Kay in his classical book on Estimation Theory [Fundamentals of Statistical Signal Processing Vol-1]. This can be easily implemented in MATLAB using Moore Penrose Pseudo Inverse or pinv(H). This is much more stable than going for the direct inversion methods.

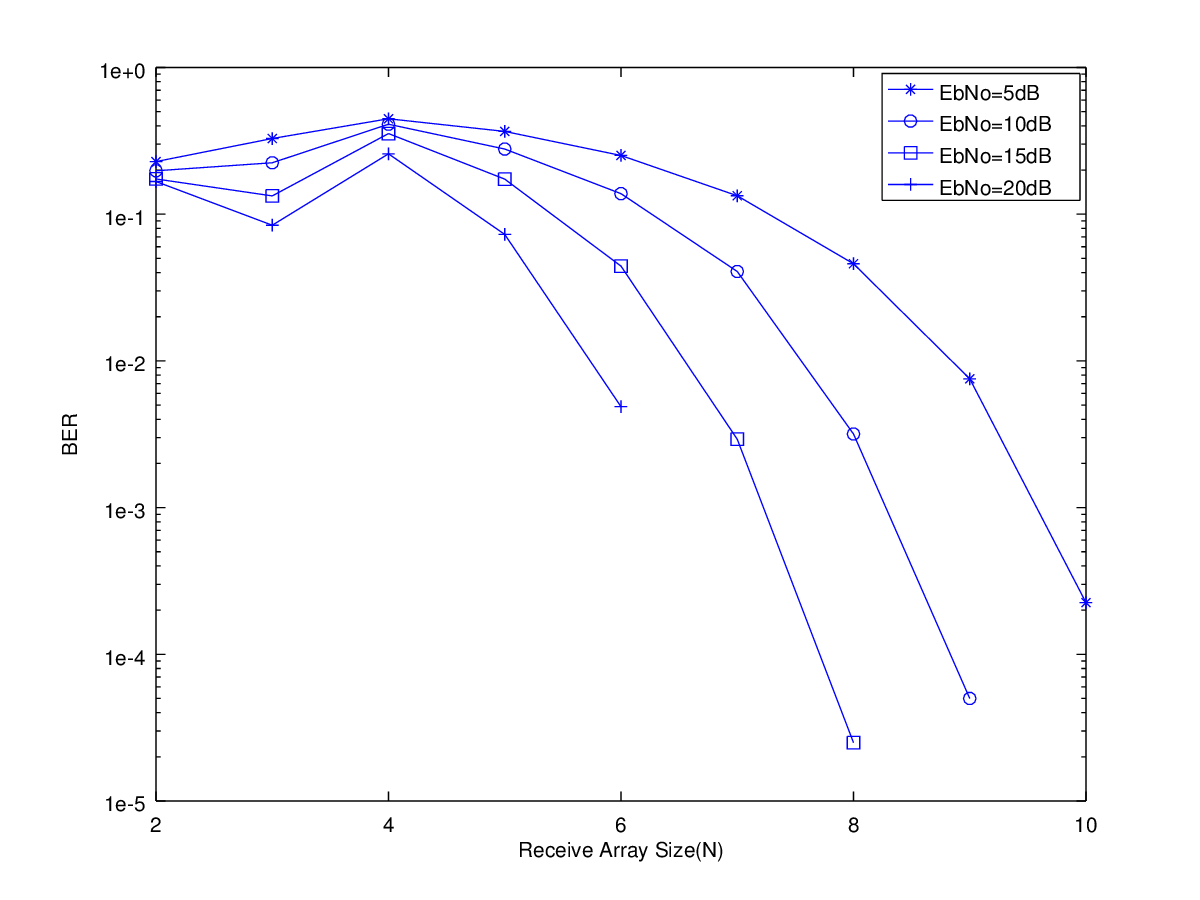

We next plot the Bit Error Rate (BER) using the code below. The number of receive antennas is varied from two to ten while the number of transmit antennas is fixed at four. The transmit antennas are assumed to be positioned at 30, 40, 50 and 60 degrees from the axis of the receive array. The receive antennas are separated by λ/2 meters. The frequency of operation is 1GHz but it is quite irrelevant to the scenario considered as everything is measured in multiples of wavelengths. The Eb/No ratio (roughly the signal to noise ratio) is varied from 5dB to 20dB in steps of 5dB.

As expected the BER for the two methods, other than ML, is more or less the same and decreases rapidly once the number of receive antennas becomes greater than number of transmit antennas (or number of signals). The case where the number of receive antennas is less than number of signals (equal powered and with a small angular separation) is dealt with by Overloaded Array Processing (OLAP) techniques and have been discussed in detail by James Hicks [Doctoral Dissertation] a student of Dr. Reed at Virginia Tech.

Strangely enough it is seen that the overloaded case is not the worst part of the BER curve. The worst BER is observed when the number the number of transmit and receive antennas is the same (four in this case). In other words the BER gradually increases as the rank of the channel matrix increases and then decreases once it reaches its maximum value. This is quite interesting and obviously has to do with Noise Enhancement that we discussed earlier. This will be further investigated in future posts.

For further information on the above methods visit this interesting article.

Update-1

So we struggled for a while to find out why the BER is worst at full rank and thought that there is something wrong in our model but ultimately we found that this has to do with how the pseudoinverse works and the way the tolerance limit (tol in MATLAB) for the singular values is set. We have found quite interesting results while experimenting with various inversion methods and the results are pending publication. Will keep you updated about the progress.

Update-2

We experimented with the MATLAB function pinv by changing the tolerance parameter. Previously we had used the default tolerance that is built into the function pinv. The default tolerance (tol) is defined as:

tol = max (size (H)) * sigma_max (H) * eps

where sigma_max (H) is the maximal singular value of channel matrix H

and eps is the machine precision.

More precisely, eps is the relative spacing between any two adjacent numbers in the machine’s floating point system. This number is obviously system dependent. On machines that support IEEE floating point arithmetic, eps is approximately 2.2204e-16 for double precision and 1.1921e-07 for single precision.

So back to the subject we experimented with two values of tol; 1.0 and 0.1 while changing the signal to noise ratio. The number of transmit antennas (users) is fixed at 4 while number of receive antennas is varied from 2 to 8. For tol value of 1.0 it is seen that changing the value of EbNo does not change the results much up to 6 receive antennas but after that the BER results rapidly diverge. For tol value of 0.1 the results are quite unexpected. The BER drops with increasing number of antennas up to N=5 but then there is an unexpected increase in the BER for N=6. This needs to be further investigated.

MATLAB CODE USED TO GENERATE ABOVE PLOT

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

% MULTIUSER DETECTION USING

% A UNIFORM LINEAR ARRRAY

% AKA RECEIVE BEAMFORMING

% COPYRIGHT RAYMAPS (C) 2018

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

clear all

close all

% SETTING THE PARAMETERS FOR THE SIMULATION

f=1e9; %Carrier frequency

c=3e8; %Speed of light

l=c/f; %Wavelength

d=l/2; %Rx array spacing

N=10; %Receive array length

theta=([30 40 50 60])*pi/180; %Angular placement of Tx array (users)

EbNo=10; %Energy per bit to noise PSD

sigma=1/sqrt(2*EbNo); %Standard deviation of noise

n=1:N; %Rx array vector

n=transpose(n); %Converting row to column

M=length(theta); %Tx array length

% RECEIVE SIGNAL MODEL (LINEAR)

s=2*(round(rand(M,1))-0.5); %BPSK signal of length M

H=exp(-i*(n-1)*2*pi*d*cos(theta)/l); %Channel matrix of size NxM

wn=sigma*(randn(N,1)+i*randn(N,1)); %AWGN noise of length N

x=H*s+wn; %Receive vector of length N

% PINV without tol

% y=pinv(H)*x;

% PINV with tol

y=pinv(H, 0.1)*x;

% DEMODULATION AND BER CALCULATION

s_est=sign(real(y)); %Demodulation

ber=sum(s!=s_est)/length(s); %BER calculation

Basics of Beamforming in Wireless Communications

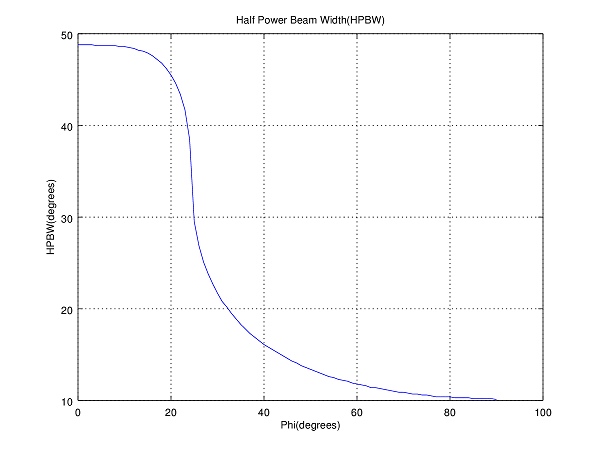

In the previous post we had discussed the fundamentals of a Uniform Linear Array (ULA). We had seen that as the number of array elements increases the Gain or Directivity of the array increases. We also discussed the Half Power Beam Width (HPBW) that can be approximated as 0.89×2/N radians. This is quite an accurate estimate provided that the number of array elements ‘N’ is sufficiently large.

But the max Gain is always in a direction perpendicular to the array. What if we want the array to have a high Gain in another direction such as 45 degrees. How can we achieve this? This has application in Radars where you want to search for a target by scanning over 360 degrees or in mobile communications where you want to send a signal to a particular user without causing interference to other users. One simple way is to physically rotate the antenna but that is not always a feasible solution.

Going back to the basics remember that the Electric field pattern depends upon the constructive and destructive interference of incoming waves. If we have a vector (usually called the steering vector) that aligns the rays coming in from a particular direction we would get a high Gain in that direction. Similarly we can steer a null in a particular direction if we want to reject a particular signal. This we will discuss in a future post.

MATLAB CODE

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

% BEAMFORMING USING A

% UNIFORM LINEAR ARRRAY

% COPYRIGHT RAYMAPS (C) 2018

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

clear all

close all

f=1e9;

c=3e8;

l=c/f;

d=l/2;

no_elements=10;

phi=pi/6;

theta=0:pi/180:2*pi;

n=1:no_elements;

n=transpose(n);

X=exp(-i*(n-1)*2*pi*d*cos(theta)/l);

w=exp( i*(n-1)*2*pi*d*cos(phi)/l);

w=transpose(w);

r=w*X;

polar(theta,abs(r),'b')

title ('Gain of a Uniform Linear Array')

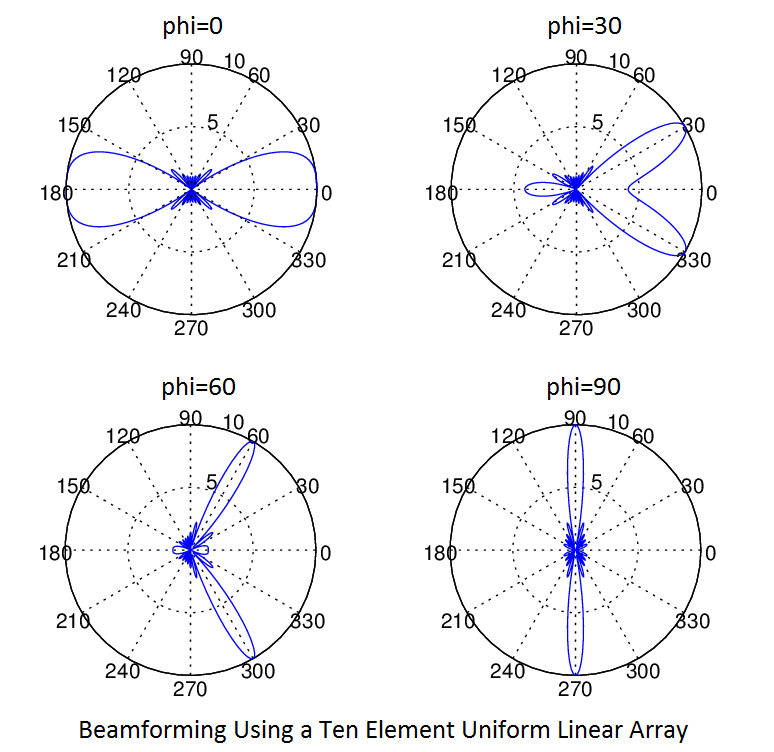

The figure below shows the Electric field pattern of a 10 element array steered towards 0, 30, 60 and 90 degrees respectively. We see that selectivity of the array is higher on the Broadside than on the Endfire. In my opinion this has to do with how the cosine function behaves from 0 to 90 degrees. The rate of change of cosine function is much faster around 90 degrees than at 0 degrees or 180 degrees. The slowly changing cosine in the latter case causes a wide response on the Endfire.

We did calculate the HPBW for a range of steering angles and found that it varied widely from as small as 10.17 degrees to as large as 48.62 degrees. This shows that simple Beamforming using a steering vector has its limitations. The detailed results along with a graph are shown below. It is seen that as the steering angle increases from about 20 degrees there is a sudden decrease in HPBW. For one degree increase of steering angle (phi) from 24 to 25 degrees there is decrease of approx 9 degrees in HPBW. We will investigate this further in future posts.

Case 1: phi = 0, HPBW = 48.62 deg

Case 2: phi = 30, HPBW = 21.69 deg

Case 3: phi = 60, HPBW = 11.75 deg

Case 4: phi = 90, HPBW = 10.17 deg

For further visualization of the variation in antenna pattern as a function of the steering angle please have a look at this Interactive Graph. The parameters that can be varied include the angle of the beam, number of antenna elements and separation of the antenna elements. This is taken from an excellent online resource by the name of Geogebra. For further information on how you can use this tool for your own mathematical problems please do visit their website.